Return of the Kradschützen TruppenIn the early 1970s the threat posed to NATO and the European states from the Soviet Union and the Warsaw Pact was seen to be growing. With the introduction of the new T-64 Main Battle Tank (MBT) to the existing large numbers of T-55 and T-62 MBTs already in service and the reports of a new T-72 following on, complimented by growing numbers of other armoured forces including the new BMP-1 Infantry Fighting Vehicles (IFVs), the Soviet conventional threat was stronger than ever.

As part of NATO’s “flexible response” strategy, the Bundeswehr expected to most likely have to first fight an intense conventional fight against a Soviet combined arms onslaught before potentially having to resort to the nuclear option. Obviously, the goal was to avoid this escalation if at all possible.

In the case of the Heer (German Army), part of their response was to create a strong, flexible force able to provide a resilient capability aiming to be able to contain the conventional fight and thus forestall a nuclear option. Part of this included the adoption/development of new materiel, such as the HOT and MILAN anti-tank guided missiles (ATGMs). These would be a major improvement over those earlier ATGMs such as the Cobra and SS.11 and would be used in both infantry roles and also fitted to armoured vehicles such as the new Marder IFV and Raketenjagdpanzer Jaguar 1 tank destroyers.

A key development was also the adoption of the anti-tank helicopter. The latter would eventually realised in the form of the Bo 105 PAH-1 (Panzerabwehrhubschrauber, "anti-armor helicopter") armed with six HOT missiles. Not only were these able to carry a powerful punch but because of their speed, they were able to offer great flexibility including an ability to be moved to wherever they were needed with speed. On the ground there was also the return of an old weapon system offering similar powerful punch and speed. This would be the motorcycle with sidecar.

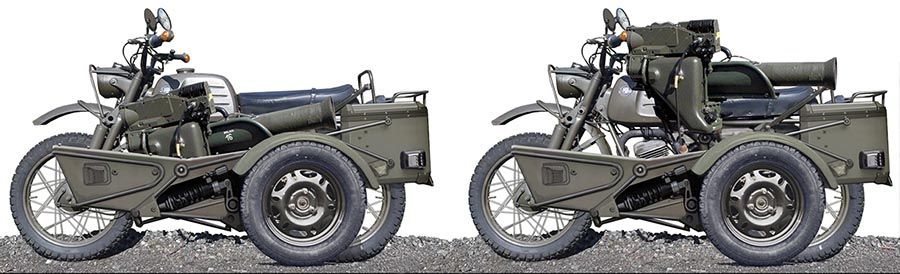

Specifically, the new Hercules K 125 BW motorcycle was adapted to have a side car of sorts. These Panzerabwehrmotorrad as they were named were not to hold people other than the rider. Rather, each simple sidecar was fitted with a MILAN Launcher and up to 4 reloads. These were issued to the new light infantry brigades, in the form of specialised platoon sized groups. The operators of such were referred to as Kradschützen Truppen, a revival of the WW2 term of their predecessors. Two variants of this new structure were originally envisioned. The first - der Waffenträger - had to accommodate a crew seat, an MBB swing-arm mount for the MILAN launcher, missile reloads, and a fuel can (großer Blechkanister). The second - der Begleiter - carried more MILAN reloads but its swing-arm mount was now for a covering-fire MG3 GPMG.

In operations, the Kradschützen Truppen would typically operate in Gruppen (squads) of 12 troops. These would include 6 Panzerabwehrmotorrad (Waffenträger) armed with MILANs and another 6 standard K 125 motorcycles for troops armed with conventional infantry weapons. It was usual for the riders to operate in pairs with one Panzerabwehrmotorrad paired with a conventional motorcycle, the operator of which would provide support and protection to the MILAN operator. The Begleiter variant was not really used in meaningful numbers. The standard engagement practice would be for the MILAN launcher to be prepared for firing. The Begleiter (or escort) would provide overwatch until guidance control was complete. Then, the pair would depart in the opposite direction to firing as rapidly as possible. Once a new and undetected firing position had been established, the procedure would be repeated.

Over the next 20-25 years the Kradschützen Truppen would provide a vital, though luckily never tested, part of the Heer’s planned response to a Soviet attack. Come the ending of the Cold War and the re-unification of Germany in 1991, the need for the Kradschützen Truppen would go away and the units were disbanded.